How To Stress-Test Your Hamstring Recovery Plan Before It Fails

Quick answer (for when you're panicking)

Guidance from an orthopaedic physician for athletes with proximal hamstring avulsion.

It’s normal to feel an identity shock when training stops and your life suddenly feels on pause. In clinical work with serious athletes, this phase is often harder psychologically than the diagnosis itself, because your routines, roles, and sense of self disappear before your body has a chance to rebuild. The evidence shows that both surgery and rehab paths involve long, uneven timelines with predictable risks, which is why “just picking something” rarely restores confidence or identity. The core answer is that feeling lost right now does not mean you’re failing - it means you’re in the middle of a real athletic transition. Your identity doesn’t come back all at once; it’s rebuilt through structure and proper rehabilitation.

What usually matters is how you engage with the process. Outcomes tend to improve when athletes treat recovery like a professional project, stress-test plans in advance, and focus on repeatable behaviours rather than waiting to “feel normal” again. Clinicians see better psychological and functional recovery when identity is built around actions, not labels. Identity is practiced, not granted.

If you’ve just been told you have a serious hamstring rupture or proximal hamstring avulsion and you’re scrolling between “have surgery” and “try rehab,” the surgery vs rehabilitation decision for proximal hamstring avulsion can feel impossible.

Start by getting your feet under you:

Join the free Athlete Transition Lab Community so you’re not thinking this through alone.

Download the Understanding Proximal Hamstring Avulsion Guide (UPHAG) so you can see the whole landscape in one place.

This article zooms in on one thing only: the actual decision between surgery and conservative care – why it feels impossible, what the spectrum really looks like, and what has to be in place before you can choose your path with a clear head.

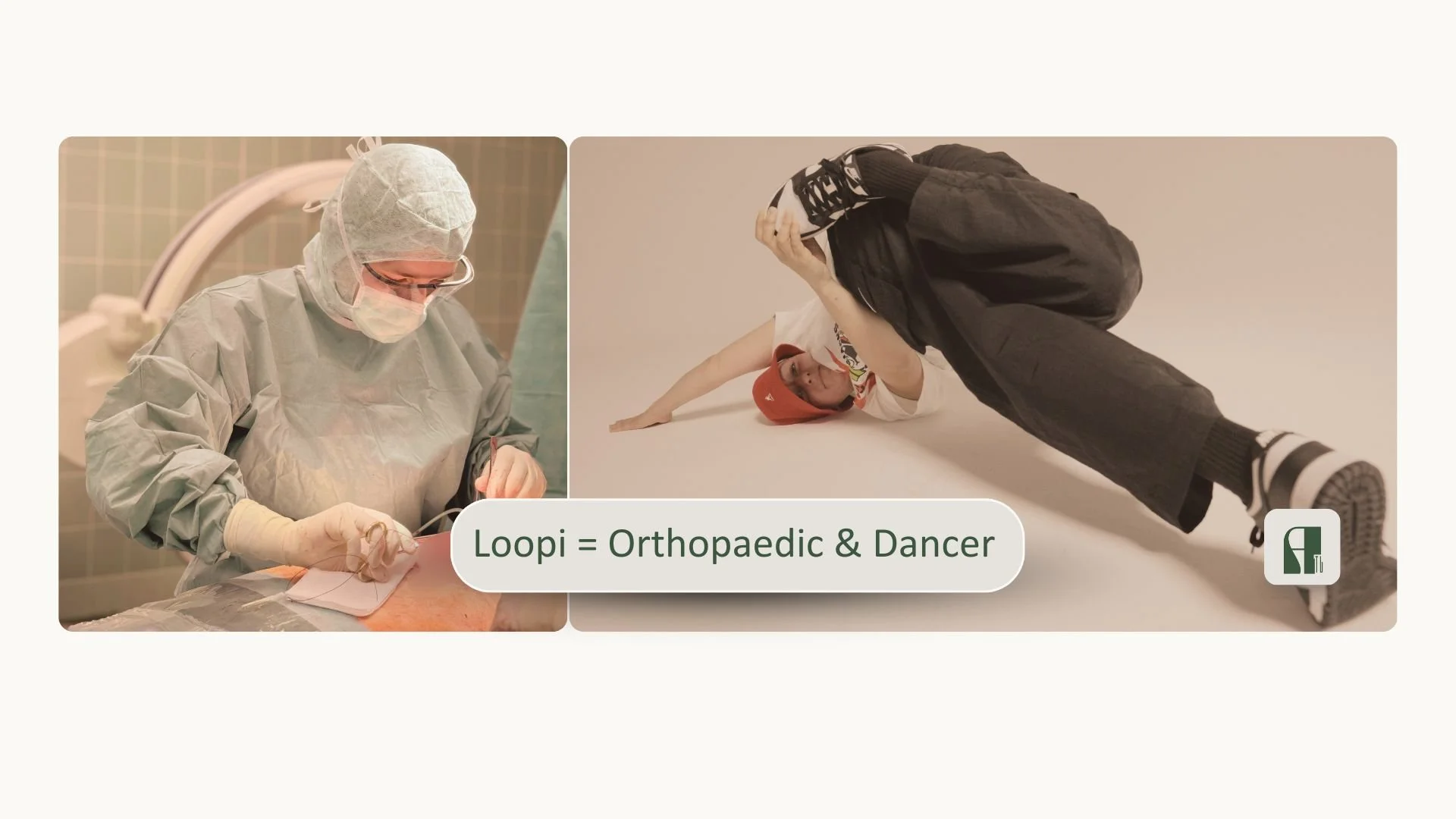

Author: Dr. Luise “Loopi” Weinrich

Board-certified orthopaedic physician with focus on athletes, decision‑support specialist for serious proximal hamstring avulsion injuries. Former high‑level athlete helping other athletes navigate complex surgery‑versus‑rehab decisions without unnecessary uncertainty, blame, or panic and their return-to-sport.

Last updated: January 4rd 2026 | Next scheduled review: July 2026

Link to author bio page with full qualifications: www.docloopi.com

Feel the identity shock when training stops and life suddenly feels on pause

Before this injury, your whole day revolved around training, competing, and moving.

Now it’s built around ice packs, appointments, and a lot of sitting still. It can feel like everyone else is getting fitter, faster, and more relevant while you’re stuck on the couch, and the sentence “Maybe I’m not really an athlete anymore” pops into your head more often than you’d ever say out loud.

On paper this is “just” a proximal hamstring rupture, but in your mind it’s tearing through your place in the team, your friendships, your routines, and even the way you think about yourself as a person. A quiet part of you is afraid that this frozen, paused version of your life might be the new normal, and that needing help with basic things means you’ve somehow given up your right to call yourself competitive.

This article exists to call that identity shock by its real name and to show you practical ways to rebuild who you are while your body does the slow work of healing, instead of waiting for some magical moment where you suddenly feel like “your old self” again.

See how data reveal predictable risks on both surgery and rehab paths

If you stress-test your options against the published numbers, it becomes obvious that both surgery and conservative treatment have predictable failure modes you can plan around.

Surgical series report many athletes returning to sport somewhere between 4 and 9 months, with good outcomes in severe cases (Allahabadi et al., 2024), but also document complication rates around 10-15% overall and a smaller percentage of major problems such as nerve issues, clots, infection, re-tear, or need for revision (Lawson et al., 2023). Conservative cohorts show that some middle-aged and recreational groups reach similar 2-year function to surgery (Pihl et al., 2024), yet also that a subset live with persistent sitting pain, strength loss, limits in high-end sport, or eventually opt for late surgery when function stays unacceptable (Mendel et al., 2024). Grey-zone and shared decision-making studies further show that delaying a decision by a few weeks for counselling and a serious rehab trial does not automatically close the surgical door (van der Made et al., 2022; Spoorendonk et al., 2024), but that waiting many months without structure can make both technical repair and psychological recovery harder (Rust et al., 2014).

What this means is that the data push back on the gut story that "as long as I pick something, it'll be fine"; they show that each path can fail in specific, foreseeable ways, which is exactly why it's worth doing a premortem on your plan before you commit.

For general information about what having surgery involves, you can read the NHS overview on surgery.

Use a premortem model to stress-test each option before committing

In The Obstacle Is The Way, Ryan Holiday suggests that real strength comes from looking straight at what could go wrong and using that information to plan better, not from pretending everything will be fine.

A premortem is just that applied to your hamstring: you imagine it is 12 months from now and surgery was a disaster or rehab was a disaster and you list what actually went wrong on each path.

James Clear’s Four Keys to Behavior Change model (make it obvious, attractive, easy, and satisfying) gives you a checklist to stress‑test both options: does your proposed surgery or rehab plan have clear cues, real motivation, low friction to execution, and built‑in wins, or is one or more of those missing?

When you see that many failed outcomes share the same weak points: no clear milestones, no realistic rehab system, no backup plan if progress stalls, you can design stronger versions of each path before you commit, instead of discovering the holes the hard way.

What this means is that, instead of asking “Which path sounds better today?”, you’re asking “Which path can I design in a way that realistically survives the next 12–24 months of my actual life?”.

Reclaim your athlete identity by thinking like a professional investor about your body, not a scrapyard owner.

Good, this is exactly the kind of parallel that lands with serious people.

Here’s a version you can drop into the HSCA or fit-checker page as its own block, still in my voice, no hype, but sharp:

“Rich body” vs “poor body” decisions

In Rich Dad Poor Dad, Kiyosaki’s core point isn’t “buy property.”

It’s: smart investors do their due diligence before they commit, not after.

A serious proximal hamstring rupture is the same class of problem.

You are not “just” choosing between surgery and rehab.

You are deciding how to invest the next year of:

Your body

Your time

Your money

Your career window and identity

There are two games you can play here:

“Poor body” decisions:

Skipping the hard questions because it’s uncomfortable

Trusting vague timelines without understanding the assumptions

Hoping things will “somehow work out” because they usually do for other injuries

“Rich body” decisions:

Doing structured due diligence before you commit

Stress‑testing the plan with clear milestones and exit criteria

Accepting the grey zone, but refusing unnecessary uncertainty

James Clear would say: identity chooses the game.

In this context, that means you can choose to be:

“The athlete who thinks like a professional about their body,”

not

“The athlete who just goes along and hopes for the best.”

Every premortem you run, every time you say

“Wait, walk me through the trade‑offs here,”

every time you use tools like the fit‑checker or HSCA to clarify the landscape before you lock in a path…

…you’re casting a vote for the rich‑body game:

patient, informed, criteria‑based decisions about a high‑value asset.

The real shift is not only:

“Which path do I take?”

It’s:

“Who am I becoming in the way I choose and build that path?”

That identity will pay off far beyond this one hamstring injury.

A mindset lesson I only learned after 300+ days of rehab

When I tore up my patellar tendon years ago, I thought I “knew” rehab.

I was a doctor. I’d been an athlete forever. I told people how to do this stuff.

Then I ended up doing my own rehab for over 300 days.

There was a stretch in the middle where I kept thinking some version of:

“Maybe my body is just done.”

“If I can’t jump or train like before, maybe I’m not really an athlete anymore.”

“If rehab was working, it wouldn’t feel this slow and messy.”

That injury is where I first really understood what Carol Dweck calls fixed vs growth mindset, without having those words for it.

My fixed‑mind version sounded like:

“My knee is ruined. I’m fragile now. I’ll never be the same.”

The “growth” version that slowly replaced it sounded more like:

“The tendon and this movement are skills I can rebuild with work and time. I just haven’t finished yet.”

Very little changed in my MRI in that moment.

But everything changed in how I saw myself.

I started using one tiny word: yet.

“I can’t land that jump yet.”

“I don’t trust this position yet.”

“I haven’t finished this phase yet.”

I also stopped reading every flare‑up as proof that rehab “didn’t work” and started treating it as data:

“OK, that was too much load for where I am right now.”

“That drill is yellow‑zone, not red‑zone – scary but useful.”

“We just learned something about timing; we didn’t learn that I’m broken.”

The other big shift was identity.

Instead of asking, “Am I still an athlete?” I started asking, “What would an athlete do today?”

Sometimes the answer was glamorous.

Most days it was:

Do the boring exercises.

Adjust the plan instead of quitting.

Ask for help instead of hiding.

That’s when it clicked for me:

Identity follows behaviour. Not the other way around.

By the time that year of rehab was over, my tendon was different, but I was different too. And now, when I work with hamstring athletes, I’m not asking anyone to pretend they’re fine. I’m asking them to believe:

“This isn’t my final state.”

“I haven’t finished this phase yet.”

“Hard doesn’t mean wrong; hard is often where the change lives.”

That was the real rehab I did on my own body. The exercises were just the vehicle.

Practice being an athlete again through small, structured actions this week

Spend this week training your identity, not just your leg.

For the next seven days, your job isn’t to somehow switch your “athlete feeling” back on; it’s to give yourself small, repeatable proofs that you still live like one. Start by writing down three qualities you admire in your best version as an athlete – for example “shows up,” “curious,” “good teammate” – and choose one tiny action per day that fits your current reality (doing the rehab you agreed with your physio, sending a message to a teammate, reading one page about this injury instead of doom‑scrolling).

Next, step into the Athlete Transition Lab Community and just watch and listen for a bit, so your brain can see in real time that other high‑level athletes feel off‑identity in this phase and are still treated as athletes, not as “former” anything.

If you notice that you’re craving more structure than “do what you can,” look at Own Your Hamstring Recovery (OYHR) and ask honestly: “Would a 24‑week plan that treats rehab like real training – with clear phases, progressions, and check‑ins – make it easier for me to keep showing up for my body even on days I don’t feel like a ‘real’ athlete?”.

By this time next week, your numbers in the gym or on the track won’t be back where they were – but you can have a short list of actions you’ve actually done, a room of people who get it, and maybe a framework to plug into.

That’s the kind of evidence that your athlete identity is something you keep voting for, not something this injury was allowed to delete.

Who this actually affects (beyond you)

When training stops and your life suddenly feels on pause, the impact rarely stays contained inside your own head.

An injury like a proximal hamstring avulsion doesn’t just interrupt physical capacity; it disrupts routines, roles, and the way you recognise yourself as an athlete. Feeling disoriented or unsure who you are without training is not a personal failing — it’s a normal response to a sudden identity interruption that happens before the body has time to adapt.

That identity shock quietly ripples outward. Your physio may see a body that is healing on schedule while you feel emotionally stuck. Your coach or teammates may assume you’re “still you,” not realising how much structure and meaning training used to provide. Your partner or family often sense that you’re grieving something intangible, even when scans or rehab plans look “fine.” Without shared language for this phase, you can end up feeling isolated in a room full of support.

You, the athlete: adjusting to the loss of routine and meaning while your body is still in limbo.

Your physio: focused on physical milestones that don’t always match how you feel about yourself.

Your coach or team: wanting you back, but not always seeing the internal transition you’re navigating.

Your partner or family: witnessing frustration or withdrawal without clear ways to help.

Questions to bring to your physio

How do you usually see confidence and identity rebuild alongside physical recovery in athletes like me?

When motivation dips even though rehab is “on track,” how do you usually adapt the process?

What signs tell you that an athlete is struggling psychologically, not just physically, and how do you support that?

How can we structure rehab so it still feels purposeful, not just something to get through?

Questions to bring to your surgeon or sports physician

From your experience, how long does this “life on pause” phase usually last for athletes?

How do you help athletes think about recovery as a transition, not just tissue healing?

What expectations tend to cause the most distress during this phase, and how can I frame them more realistically?

Where do you usually see athletes regain a sense of control, even before sport fully returns?

Questions to bring to your coach or team lead

How can I stay connected to the team or training culture while I’m not physically participating?

What would supportive involvement look like right now, without pressure to perform or rush back?

How can we communicate about progress in a way that doesn’t reduce me to my injury status?

Questions to bring to your partner or close support person

What changes have you noticed in me since training stopped?

What would help you feel more confident supporting me during this phase?

How can we talk about frustration or loss without either of us feeling like we need to “fix” it?

When you’re stuck on the surgery‑versus‑rehab decision, it can feel like everything depends on one irreversible choice.

In the background, though, most athletes are also quietly wondering whether they really understood their MRI and what life will feel like on the other side of this decision.

Seeing the diagnosis, the decision, and the recovery as one connected storyline often makes the grey zone feel less paralyzing.

It turns a single terrifying fork in the road into a sequence of smaller, understandable steps that you and your local team can walk through together.

If that’s the kind of structure you’ve been missing, the guides below can help you zoom out, steady your footing, and then move forward with more confidence.

Related articles you may find helpful:

Understanding Your Diagnosis

MRI ≠ Verdict: The Missing Pieces In Your Hamstring Decision – clarifies how MRI, symptoms, timing, nerve issues, and function shape the real decision space instead of acting as a one‑line verdict.

Making Your Decision

Stuck Between Surgery And Rehab: How To Decide Without Regretting It In 2 Years – clarifies typical surgeon reasoning, when surgery or conservative care are clearly favoured, and what “grey zone” really means for serious athletes.

Planning Your Recovery

When Every Twinge Feels Dangerous: Reinjury Fear After Hamstring Surgery Or Rehab – clarifies what recovery usually feels like after you’ve chosen a path, including common milestones, plateaus, and the “cleared but scared” phase where most people start to worry again.

Final thought

You are not weak, broken, or indecisive for struggling with this. You are being asked to move through a rare, high stakes injury with partial information, conflicting or incomplete advice, and a system that mostly cares about you walking while you care about performing and feeling like yourself again.

You cannot remove all risk or uncertainty. But you can remove a lot of the guessing and the isolation.

Your best next steps from here (if you are somewhere in rehab):

“Stop doing this in isolation.” → Join the community

Step into the free Athlete Transition Lab Community so you can see other athletes with proximal hamstring ruptures or avulsions at different stages of rehab and return. You will hear honest stories about flare ups, plateaus, and small wins, instead of trying to decide alone whether you are “behind” or “doing it wrong”.“See the whole pathway you are stuck in.” → Read PHAP (and UPHAG if you are early)

If you are already in the system – post op, in physio, or technically “cleared” but not back in your sport - the Proximal Hamstring Avulsion Pathway (PHAP) shows you the full journey from injury to long term outcomes and the predictable error moments where most people get stuck. If you are earlier in the process or still confused about the surgery versus rehab context, pair it with the Understanding Proximal Hamstring Avulsion Guide (UPHAG) so you understand both the decision landscape and the rehab lane you are in.“If surgery is done and you feel directionless.” → Consider HRRC or OYHR

If the big decision is made and your real question is “What actually happens in the next 12 to 24 weeks?”, the Hamstring Recovery Roadmap Call (HRRC) is where you turn that into a concrete 12 week plan you can follow alongside your surgeon and physio. If you already know you want a full 24 week, hamstring specific structure instead of improvising each phase, Own Your Hamstring Recovery (OYHR) is the longer runway built for that middle part of recovery. Neither replaces your local team or guarantees outcomes; they exist to give you a clear framework so every week is not a fresh guess.

By Dr. Luise “Loopi” Weinrich

Board‑certified orthopaedic physician with a focus on athletes, decision‑support specialist for serious proximal hamstring avulsion injuries. Former high‑level athlete helping other athletes navigate complex surgery‑versus‑rehab decisions and their return‑to‑sport without unnecessary uncertainty, blame, or panic.

Last updated: January 4th 2026 | Next scheduled review: July 2026

Link to author bio page with full qualifications: www.docloopi.comMedical DisclaimerEverything here is education and decision support. Nothing in this article, or in HSCA/UPHAG/Community/OYHR, diagnoses, treats, or guarantees outcomes – your own medical team always stays in charge of your care. If you’re experiencing severe pain, numbness, weakness, or other concerning symptoms, seek immediate medical evaluation.